|

|

|

|

|

THE EARLY YEARS |

|

|

|

|

| (A) |

Video Viewing and the ‘Challenge for Change’ model |

| (B) |

Video in the Mall

A Cassette Network

|

| (C) |

A Western Suburbs Transmitter |

(A)

The Model

In 1974 Australia’s Film and Television Board (FTVB) sponsored a trial in community video. A big influence behind this was ‘Challenge for Change’ – a program of Canada’s Film Board.

‘Challenge for Change’ (CfC) projects produced finished films and videos. But that was not what they were about! They fostered a process; one they developed through trial and error (hereinafter called ‘The Process’).

The Process

• With its permission the actions and opinions of a group are recorded.

• They view the recording. Are they happy how it presents them?

• They arrange to show their videotape to a second group.

• The second group views the tape and is invited to respond. Viewing is active not passive.

• In response, they in turn produce a videotape.

• A momentum builds. A community’s confidence grows

In ‘The Process’ community members are behind the camera, in front of the camera, react to the camera. You don’t have to wonder who would be an audience for this.

Videomaking and Videoviewing are inseparable.

An example – Fogo Island off the coast of Newfoundland was home to a demoralized population. There were few fish left in local waters. It was expensive for fishermen to have their catches canned.

Following ‘The Process’ two new co-operatives were formed. One set up a

fishermen-owned cannery. The other built bigger fishing boats that could travel further.

No single fish stock need be fished out.

Did ‘The Process’ by itself solve deep-seated problems? No. But it was invaluable. It helped people gain a more positive view of

• themselves

• their communities

• their ability to influence their future.

The FTVB dreamed of ‘Fogo’-like success stories springing from its 12-month venture into community video. It wasn’t going to happen.

With the need to embed video access into local life (FTVB’s other dream), there wasn’t time, there weren’t the people. Videoviewing as part of a change process through major projects remained a dream.

But not forgotten.

Fast Forward to 1976

Western Communications put a proposal to the FTVB. From Western Communication’s (rapidly shrinking) budget it would start a Special Projects Fund. The fund would be on a modest scale. Its purpose: to equip videomakers to take on major projects using

‘The Process’ pioneered by CfC.

The financial rug was being pulled out from under community access video............

‘Nope. Can’t help you.’

Forward Again to 1977 and point the satellite navagation system West

Brian Williams had left Footscray in 1975. In February 1977 he took on a CfC-type assignment in the West Australian goldfields. It recorded reactions to the closure of the Golden Mile mines in Kalgoorlie. Videotapes were recorded and played on local TV

followed by live phone-in/studio panel discussions.

|

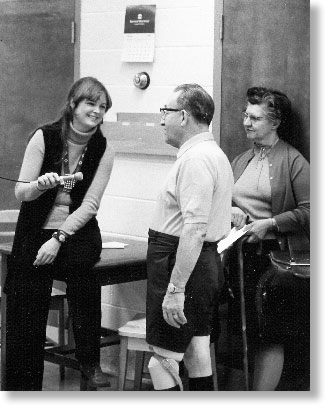

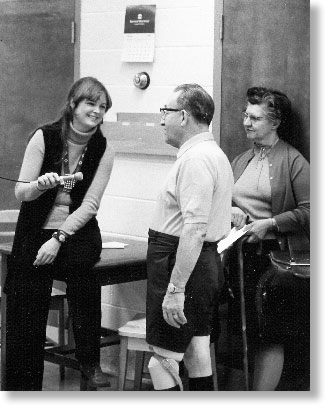

| Dorothy Henaut (left) working with Physiotherapists and their patients - Challenge for Change circa 1970 |

|

|

|

| A street screening from the back of a station wagon in Rosedale, Alberta, Canada (Challenge for Change) |

|

|

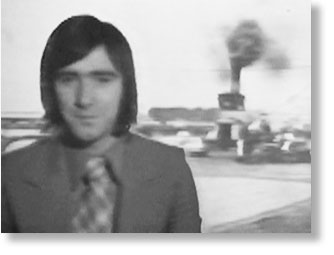

| “Goldfields Playback” - 1977 |

|

|

|

(B)

VIDEO IN THE FOOTSCRAY MALL

Alongside encouraging videomaking Footscray and Turtle Video set about providing opportunities for videoviewing.

Footscray launched into an ambitious project to run a cable down Paisley Street from its video centre to the local mall. The Mall was the thriving hub of Footscray’s shopping precinct. A large screen would show Footscray residents videos made in their suburb by Footscray people.

The proposal had FTVB and local government support. Despite Brian Williams’ infectious leadership of the project, technical problems with cabling unfortunately could not be overcome.

Video in the Mall went ahead in a different form. Booths containing recorders played continuous loops of videotape during daylight hours.

From Reel to Cassette

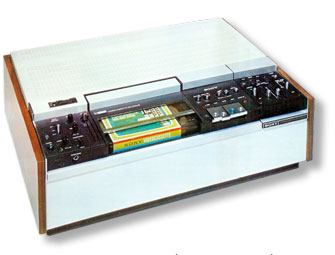

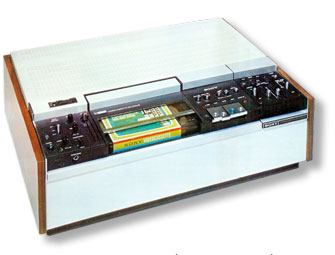

Portapaks recorded sound and image on ½” videotape reels. For a tape that would be frequently played on different machines by different people, the open reel invited both dirt and damage. Video cassettes were an obvious, more robust alternative.

The FTVB had supplied its video centres with a ¾” video cassette player. It

hadn’t supplied equipment to transfer a Footscray or an Altona videotape from a portapak reel to the larger format cassettes. ‘We can’t supply all the video centres with cassette recorders’ said the FTVB. ‘Carlton Video Resource Centre has a ¾” video cassette recorder – take your tapes there and have them transferred.’ So

we did. And that’s how we gained a stock of videotapes that could stand up to public playing.

Turtle Video established a partnership with the Altona Library. Cassettes of videos made through Turtle were available for viewing in the library during opening hours. Short features and, later, editions of Channel 4 News were

the staple diet. The link with the library and through it tacit support of Altona council, was useful. But the number who viewed the available cassette tapes was small.

Both the Mall and Library won larger viewing audiences with Footscray and Turtle coverage of two major community projects: The Saltwater River Festival and the Back to Altona celebrations.

Videoviewing venues in the first year included the Grand Theatre Footscray, the Steam Packet Hotel Williamstown, the Workingmen’s Club Altona, the Essendon Community Centre.

The Western Community media (joint Footscray/Turtle – soon to be Western Communication) submission to FTVB for a second year’s financial backing proposed an ambitious program to expand videoviewing opportunities.

We wrote:

A community videomaking program grows in effectiveness as it is

matched by a serious videoplaying program.

A specific allocation of resources is needed in the second year’s budget to:

(a) establish a regular video cassette network now;

(b) prepare the groundwork in education and training of local people for future community cable and/or broadcast video.

The proposal had three elements:

(1) A regular cassette network where videos could be viewed and/or borrowed.

(2) Events where community video could be shown and responded to – either piggy-backing on community events or the network itself creating events.

(3) A part-time staff member to foster this project.

Finance for a project worker to actively promote Videoviewing didn’t come. But Western Communications pushed on with the first two elements of the proposed scheme. (This proposal was revisited by Mac Gudgeon in 1977. He recommended an expanded version in partnership with Carlton Video Resource Centre.)

|

|

|

|

|

| Sonys VO-1810 U-matic Videocassette recorder |

|

|

|

|

CASSETTE NETWORK

The Altona Library and Community Outreach at North Williamstown remained the permanent places where Western Communications-made videos could be viewed. Other access points had videos for viewing for shorter seasons. These included:

Yarraville Community Centre

Laverton Community Centre

Footscray Community Arts

Centre

Sunshine Union Community Centre

Western Region Education Centre.

Information about this network was promoted in the regional press and through Western Communications’ quarterly news sheet ‘Where We’re At’.

Today the information would be available on a web site.

SPECIAL EVENTS

Altona videomaker Graeme Hunter made a short fiction work ‘The Puzo Incident’. It received its “world premiere” outside the milk bar on the Bayview Village housing estate where the video was made.

The Channel 4 group’s ‘John Wray McCann Shows’ were an example of Western Communication sponsored events. An audience was invited to be part of the recording. It acted as promotion for community video.

During Turtle Video’s first year a ‘Back to Altona’ celebration was sponsored by the local council. Videomaking and Videoviewing were closely linked in the community video coverage.

Railway Anniversary

The anniversary of a passenger rail service to Altona was looked forward to by local residents. A special steam train re-enactment was at the heart of the event. Western Communications planned a permanent record of the occasion. One video crew (original Turtle members Alan Dyall and Robin Kenny) were on the train interviewing

passengers.

A second crew recorded the train’s progress through the inner west.

The edited video was shown through the cassette network, then lodged with the local

Historical Society.

Pier Street Parade

The second highlight was a parade along Pier Street. The enthusiastic local response to the procession led to it becoming an annual event: a parade that began at the beach end of Pier Street and proceeded to the Cherry Lake reserve for ‘Operation Recreation’ (a family fun day).

A single videomaker recorded the first parade. The tape was played to the Historical

Society and for the next ten days of celebrations in the Turtle shop. In following years, both the event and Western communications participation grew.

In 1975 a 2-camera coverage, with a pair if commentators seated at a card table was

run from the Mayflower milk bar in Pier Street. The next year it was 3 cameras with the commentators sitting out in the street at a larger kitchen table.

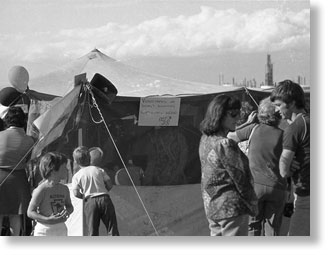

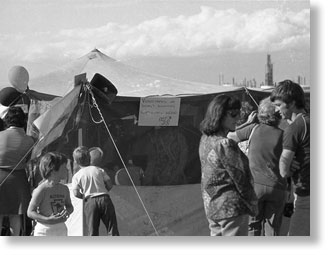

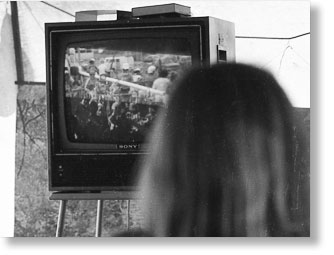

By 1981 the coverage had grown to include an amazing 2 vans, 7 cameras and a tubular scaffold platform for the commentators. To great interest, video of the parade was

shown for the rest of the day in a tent at Cherry Lake. An edited cassette of the day’s events was promoted through the local press. It was played at the Western Communications studio for the next fortnight and available permanently for viewing through the cassette network. One year, a special two hour ‘mock broadcast’

was made from Cherry Lake. As one segment was being ‘broadcast’, the next two segments were being set up.

The idea was what the Channel 4 newsgroup called ‘The Philosophy of As If’; that is, aim for standards ‘as if’ the video being made was being broadcast live to the TV screens of the western suburbs.

(What would do if community video broadcasting was here today?) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Above: Videotapes of the parade were shown in

a “video tent” at Cherry Lake |

|

|

|

|

(C)

A WESTERN SUBURBS TRANSMITTER

The early community video people in Melbourne’s west were incurable optimists. They believed that community video stations would be set up in the (not too distant) future. At least one would be based in the western suburbs.

Western Communications Cassette network was a valuable means of distributing video programs. It could be expanded and promoted further. A capacity to broadcast direct to home TV sets was the next step.

“A fly on the wall”

A discussion was in full swing at Western Communications.

The topic – distribution.

“We’re making good tapes but not a lot of people get to see them. What can we do about it?”

Arguments went back and forth. Then –

“Did you know that an aerial can act as a transmitter?”

“What?”

“Yeah. The same aerial used to receive a TV signal can also broadcast one.”

“You’re joking!”

“No!”

“I didn’t know that.”

“Not many people do.”

“You mean, if we connected a portapak to a TV aerial we could send a video we’ve made into the air and out into the world?”

“Yes.”

How does that work?

The only practical difference between a transmitting antenna and a receiving one is that the transmitting ones are designed to take a lot of power without melting. The portapaks RF unit doesn't pump out a lot of power, so it won't transmit very far, but it will transmit.

Western Communications was hungry to explore any methods to transmit community programs alongside the established ABC and commercial television channels.

Two were tried ......................................................................

PIRATE BROADCASTS

A simple transmitter was constructed. Broadcasts were made from a mobile van. They were made on the frequency of one of the commercial TV channels – after its transmissions had finished for the night.

The transmissions didn’t travel far. The audience who picked it up could have fitted into a couple of ‘phone boxes’. The action wasn’t legal.

HAM VIDEO BROADCASTS

Ham radio is well known, ham video less so. There was, however, an informal network of ham radio enthusiasts who had ventured into ham video. Several broadcasts were made from ham radio/video transmitters in the west. One from St.Paul’s School in North Altona demonstrated a capacity to reach all of the region. This was legal, but few homes had the necessary equipment to receive the signal.

These two experiments whetted the appetite for a capacity to broadcast video. But, it was understood, they were a dead end.

A transmitter would give community video the opportunity to be a force in the life of the region. It had to be legal, on an officially allocated frequency. It had to be mobile.

Western Communication’s idea was for a short-range transmitter.

It would broadcast into neighbourhoods. It could broadcast into adjoining suburbs. The signal didn’t have to reach from Williamstown to Werribee. It was considered necessary to be able to transmit from anywhere in the region.

It would be, first and foremost, part of projects in community-building and support.

People who couldn’t attend a public screening could watch at home. They could ring-in their reactions or attend a recording session at a later time.

Project focused transmissions could also include other local videos.

However it wasn’t the intention for Community TV to model itself on 24/7 Lifestyle programming.

Legal community broadcasting required frequencies being available to carry the signal. Technical and political hurdles had to be jumped over for this to happen.

In 1975 Western Communications submitted a proposal to conduct a research project on distribution in general and broadcasting in particular.

The FTVB’s and DURD’s response ?................................silence.

(Translation – “If there’s research to be done, we’ll do it!”)

For a while, hopes for community video broadcasts lay dormant.

In 1980 Western Communication’s Peter Duffy wrote:

The establishment of community television broadcasting in Australia has been the long-held wish of people who have been involved with the whole access programme since its inception.

One very obvious threat to a metropolitan-wide community access television station which is partially government funded is the establishment of small stations such as suggested by Westcom. However, Westcom feels that a small station would better serve community needs.

|

|

|

|

|

A local concert recorded “as if” it was being

broadcast live - 1975 |

|

|

|

Channel Four News was broadcast from Altona North

to Brighton via ham video |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|